Drew Horton, Enology Specialist – University of Minnesota Grape Breeding & Enology Project

One of the most important things you can do for your new wines right now is to take the proper steps to maintain their freshness. After a long year of nurturing your vines in the vineyard, and a few weeks turning their fruit into wine, now is the time to do your best to keep those wines in as optimum condition as possible during maturation and in preparation for bottling.

Maturation or aging of your wines in bulk storage is extremely important. Without proper care and maintenance, fresh, fruit-forward and youthful wine can quickly develop into a tired, oxidized and spoiled mess. There is often a misperception among novice winemakers that once a wine is fermented and racked, that merely putting the wine into barrel or tank storage will cause the wine to magically improve over time, and often for too long of a time. Though it is true that some maturation time will help the wine’s flavors and aromas to develop and “marry”, without proper control of the maturation environment a wine can change, degrade and spoil quickly.

The best friend a winemaker has at this time of year is sulfur dioxide (SO2), in the form of KMBS or potassium metabisulfite powder. There is a lot of talk going on lately about “natural wines” and the idea that the use of no or little sulfur will produce a truer or purer wine. If you are someone who likes to take chances, then go ahead and don’t use sulfur. However, if you are attempting to conduct a sustainable business that depends on a fresh, consistent, and quality product, then the judicious and proper use of sulfur is essential.

The best thing I learned while working for the world’s largest winery company is the addition of a 60 ppm dose of sulfur immediately following the completion of fermentation. That is for white wines, once primary yeast fermentation is complete, and for reds, after completion of primary and secondary (malo-lactic) fermentation. Add a dose of 60 ppm of KMBS and mix well into your wine after final transfer or racking to a storage vessel (barrel or tank).

This prophylactic high dose of SO2 will work quickly to kill or inhibit any spoilage bacteria or yeasts that may exist in your fermented wines, much like a “shock dose” of chlorine in a swimming pool.

The next considerations for the proper maintenance of stored wines are storage temperature and the need to keep vessels full. A wine in maturation-storage should be kept at 60°F or below, 55°F is best. Do your best to keep your wines in completely full vessels with little or no head-space. It is preferable to have a wine stored in various smaller vessels that are completely full than in one large vessel with too much head-space.

If you absolutely cannot avoid headspace in a vessel, then do your best to manage that space by weekly visual inspections of the wine’s surface, the regular use of an inert gas (nitrogen, argon, or CO2) to displace air (and oxygen), and to keep a proper level of free-SO2 in the wine, based on the wine’s pH. The higher the pH, the more SO2 is needed to do its job.

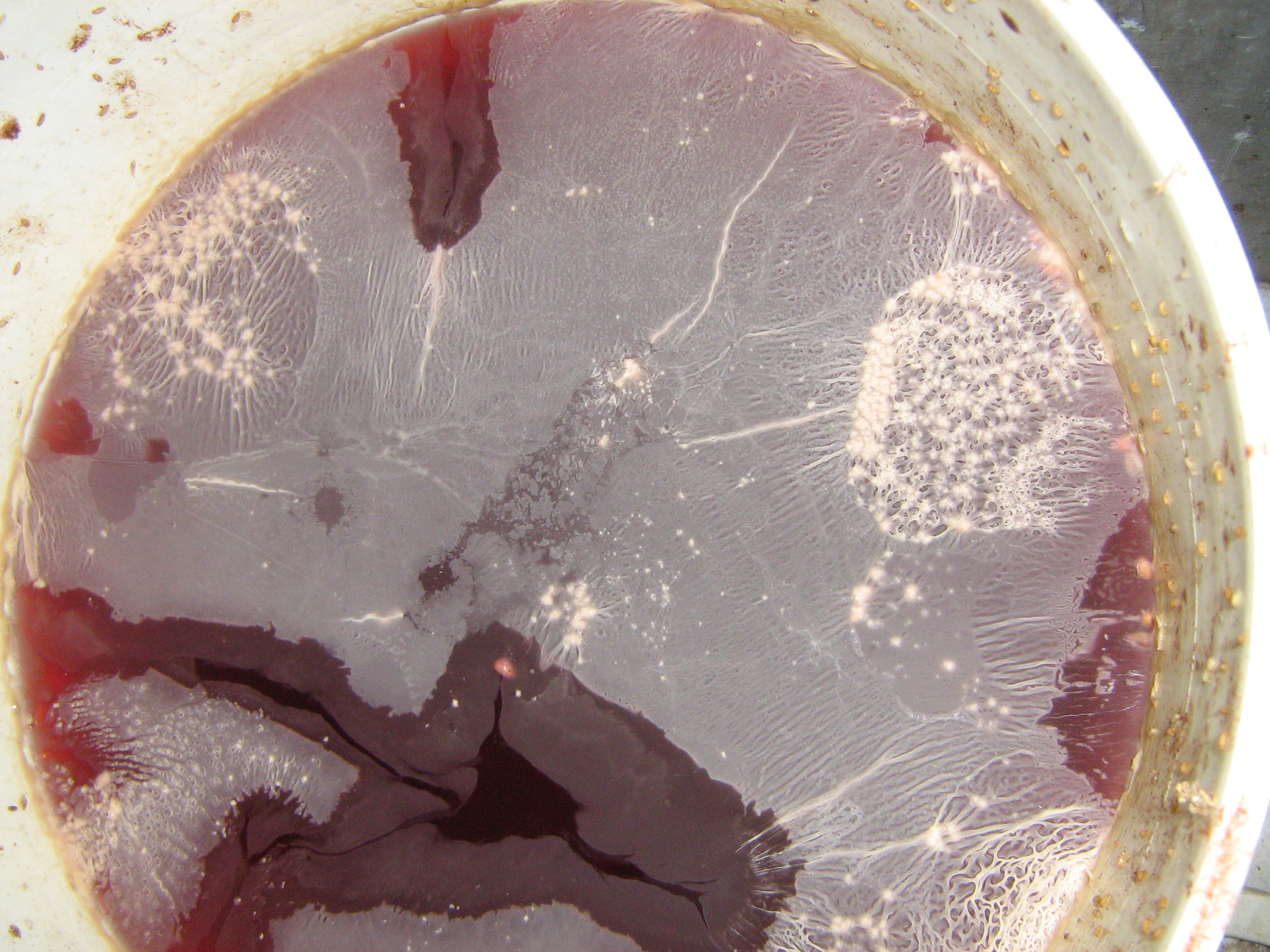

The reason to visually monitor the surface of a wine in storage is to ensure that no surface yeasts or molds are forming, which can lead to spoilage or increase of volatile acidity (vinegar smell). Should you notice a surface yeast or mold forming, the best thing to do is to sterile filter the wine as soon as possible to lower or eliminate the bacterial load, and to keep a proper level of free SO2 by checking it and adding it every 10 days or so.

These film yeasts can form powdery or waxy-looking surface scum on stored wine (Figure 1), and anything that is forming or floating on the surface of a stored wine should be avoided or treated. One can use a few grams of KMBS dissolved in water and applied with a spray-bottle over the surface of the wine as a way to slow-down the bacterial spoilage activity before a re-transfer or filtration.

Certainly most wines need some maturation time, and indeed some robust reds can benefit from extended barrel-maturation for up to 2 years or more, however, a stored wine is not to be forgotten. In tank or barrel storage, the wine needs to be constantly monitored and maintained with SO2. Head spaces need to be “sparged” with inert gas on a regular schedule, and a watchful eye kept on the surface of the wine. For wine in barrels, monthly topping and SO2 maintenance, and a full rack-and-return procedure once or twice a year is highly recommended.

Now is the time to take the steps necessary to insure all your work and effort will be preserved and ready to thrill your customers with your fresh and vibrant new wines.

A chart showing proper molecular SO2 rates by pH level can be found here:

http://srjcstaff.santarosa.edu/~jhenderson/SO2.pdf

And a handy on-line SO2 addition calculator can be found here:

https://www.winebusiness.com/tools/?go=winemaking.calc&cid=15

If you have any questions or comments, feel free to contact me directly at [email protected], and I will do my best to help, or help to find the answers to these and any other winemaking challenges.